Budgeting is hard.

I’m a financial planner and I’ve helped hundreds of people with their own personal budgets. You would think that naturally, I would be great at budgeting.

I’m not.

Now that I’ve worked on it and figured out what works for me I am, but I wasn’t naturally that way. None of us are.

I can remember many specific times as a financial planner that I felt insecure talking to people about their budgets because I didn’t have a great system for doing my own budget. Even though I “knew” all the right things, budgeting used to be difficult for me.

It was only through dozens of attempts at different systems, apps, and programs that I finally realized something. Budgeting is tough. But not because we don’t try hard enough or don’t know the right things.

It’s tough because we approach it the wrong way. We rely way too much on discipline and will power in our budgeting and that just doesn’t work out for most of us.

We need an appropriate system that works with our natural tendencies instead of against them.

So even though I failed many times trying to create a system that worked for me, I realized something important in the process.

I realized the goal of budgeting should be to design a system that allows me (and you) to think about money as little as possible.

If done correctly, budgeting should be something that we don’t really have to think about a whole lot.

During this time, and after working with hundreds of people, I also saw that all of us have a natural tendency to spend whatever money we have.

For example – if we only have $100 to spend then we will find a way to only spend $100.

But if we have $10,000 to spend then we still have a tendency to spend it all.

This is called Parkinson’s Law.

Here’s the problem with that – let’s say your monthly take-home income is $10,000. You don’t actually have a full $10,000 to spend.

A lot, if not most, of that money is already accounted for with your various financial commitments (i.e. mortgage/rent, phone bills, insurance, etc…).

So the way Parkinson’s Law shows up in our financial lives is we spend as if we have $10,000 but the reality is we have a lot less once we deduct the expenses that have already been accounted for.

I saw the need for a system that would help me budget without having to think about it too much, but would still prevent me from my tendency to overspend.

Once I clearly saw how this was impacting my finances I slowly began to build a simple system that created two things for me – Clarity and Constraints.

Step 1 – Create Clarity

In order to figure out how much of my monthly income I actually had available to spend, I needed to start by creating clarity on my expenses. I did this by separating my expenses into one of three different categories:

- Recurring fixed expenses

- Recurring non-fixed expenses

- Discretionary expenses

Fixed Monthly Expenses

Recurring expenses are expenses that you have already committed to and they are typically in the same amount each month. A few examples of recurring expenses:

- Mortgage/rent

- Cell phone bills

- Utilities

- Gym memberships

- Insurance payments

- Cable/Netflix/Hulu

- Etc…

These are the expenses that you will pay even if your credit/debit card never leaves your pocket. If you want a more comprehensive list of these expenses so you can follow along with this exercise then here’s a spreadsheet that will allow you to do so: Budget Template

It’s crucial to know these expenses because this shows how much of your monthly income is already committed and not free for you to spend.

Going back to our previous example, let’s assume your take-home income (i.e. after taxes and deductions) is $10,000. When you add up your recurring fixed expenses let’s assume that number is $6,000.

That means that you really only have $4,000 of your $10,000 monthly income to spend because the other $6,000 has already been spent for you (by your past self).

Non-fixed monthly expenses

This brings me to the second category. I had to figure out my recurring non-fixed expenses. These are things I need to pay for each month to live, but they aren’t commitments that I’ve already made like rent or a phone bill is.

These are typically things like groceries or gas. I need groceries to eat and I need gas to get to where I want to go. But I could overspend on groceries, whereas it would be difficult for me to overspend on rent. That’s why I have these in a separate category.

So these are things I do spend money on each month, but the amounts vary.

Let’s assume in this example you spend $700 per month on groceries and $300 per month on gas.

Now we know that of the $10,000 you take home each month $7,000 of this needs to be committed to essential expenses, leaving $3,000 for other expenses.

Discretionary Expenses

The last of the three main categories of expenses are discretionary expenses. These include things like dining out, entertainment, shopping, Amazon purchases. You know, the typical things that absolutely destroy our best attempts at budgeting.

None of these expenses are bad, but we need to have a budgeting system that does two things – 1.) Shows us how much we can spend in these categories and 2.) Makes it easy to monitor how much we have remaining in the month to spend on them.

In our example, it looks like we should have $3,000 to go spend on dining out, entertainment, and other fun things like that.

Not quite.

There are two categories that we haven’t covered quite yet.

One-off Expenses

I can’t tell you how many times my monthly budget was working perfectly until I had to go to the dentist or put new tires on my car.

These were expenses that I didn’t account for in my normal monthly budget so when they came up, I either had to pull money out of savings or put them on a credit card and worry about them the following month.

After several of these frustrating experiences, I finally realized something. One-off expenses really aren’t all that “one-off”. They seem to happen almost every month!

These are things like car repairs, auto registration, Christmas gifts, wedding gifts, baby shower gifts, insurance premiums if not paid monthly, vacations, dentist/doctor bills, property taxes if they aren’t impounded, Stagecoach Music Festival tickets (this is a big one in our household), etc….

You see what I mean? There are tons of these things.

I realized I needed a better way of planning for these “one-off” expenses. I didn’t like pulling from my emergency fund to pay for them. I like to reserve that for emergencies.

And if I put the expense on a credit card then it saved my monthly budget for the current month, but only by ruining next month’s budget.

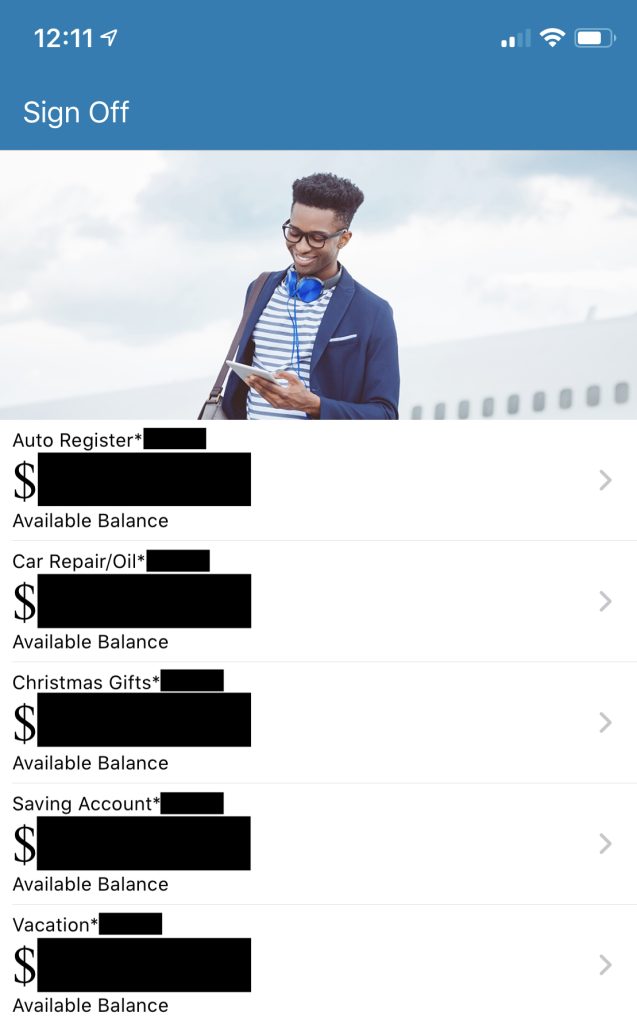

What I did instead is I set up sinking funds for the larger one-off expenses that knew would come up. A sinking fund is just an account where we could set aside money each month so that by the time I had to pay for the expense I already had the money set aside to do so.

For example, let’s say you want to save for a $5,000 vacation one time every year. You could set aside $416 every month for 12 months so that at the end of every year you would have $5,000 that you could use to go pay for your vacation without just putting it on a credit card (and then return home miserable because now you have to figure out how to pay it off).

What I did is I looked at all of these categories that my wife, Ashlyn, and I have – gifts, vacations, auto registration, car repairs, etc… Then we determined how much we wanted to have for each of these expenses each year. Then we divided that number by 12 so that we knew exactly how much we need to set aside each month to pay for them.

We then opened up separate high-yield saving accounts for each expense at a separate bank. We used Barclays for this, but there are several of these types of banks to choose from.

It was important to me that I open these accounts at a separate bank for two reasons –

- Having these accounts at separate banks makes it less likely we will “cheat” and spend that money on something else. Those accounts are out of sight out of mind. Plus, it’s more difficult to access that money so I can’t “accidentally” spend it in a moment of weakness.

- I earn interest. These are all expenses that only happen once every few months or once per year. If I’m going to let my money sit around for that long then I want it to be earning interest for me.

Here’s a snapshot of our accounts so that you can see what I mean:

Once you know how much you need to save each month for each of your recurring expenses, the next step is to add that number up. Once you have it, that’s a number that I would add back into the fixed monthly expenses.

I would encourage you to treat these savings as a fixed commitment.

Assume that between vacations, gifts, car registration, and whatever other categories you have, the total you need to set aside each month is $500.

If we go back to our example, you would add that back into your fixed expenses. So instead of $6,000/month that would really be $6,500/month.

Which means that instead of having $3,000/month left for discretionary expenses you really have $2,500 left for discretionary expenses.

Investing/Savings

The other thing that hasn’t been accounted for yet is saving and investing.

Now if you’re doing all of your savings through your 401(k) plan or another program through work then that’s been accounted for already. The $10,000/month of net income is after your 401(k) contributions have already been made.

But if you want to do any other type of saving or investing, that’s something that should also go into your fixed monthly expenses.

Let’s say in this example you want to save $1,000/month for a home and $500/month to Roth IRAs, so $1,500 total.

Now your fixed monthly expenses go from $6,000 as a starting point, to $6,500 after we include our sinking fund contributions, to $8,000 after we include our other saving/investment contributions.

Back to Parkinson’s Law

This is why this exercise was so helpful for me.

I mentioned that our tendency to spend whatever money is in our checking account can be attributed to Parkinson’s Law. Well if we view this hypothetical $10,000 income our checking account as “spendable” then we’re in real trouble.

The reality is $8,000 of that is already “spent” on recurring monthly expenses and another $1,000 will be spent on groceries and gas. That means that $1,000 of that $10,000 can actually be spent without sacrificing any other areas of your financial life.

This gave me permission to go ahead and spend that leftover “discretionary” amount on whatever I wanted as long as I didn’t spend any more than that.

That’s where I got when I finally looked at things clearly. I had created clarity after going through this exercise and fully seeing my income and expenses.

But the last step for me had to do with how I implemented this.

Step 2 – Create Constraints

I could go through all of the steps above and have perfect clarity as to how much I “should” be spending, but still blow my budget by swiping my credit card on whatever I wanted.

Like I said at the beginning, it’s not enough to know what to do, I needed a system to help me implement this without having to maintain incredible discipline or focus on it 24/7.

I needed to build a system of guardrails around my spending. I had to “James-proof” my budget.

I realized that the only way to do this for me was to stop spending using a credit card. Using credit cards required too much effort for me to keep track of my spending.

With a credit card, I had to track this month’s expenses that I would pay for with next month’s money while trying to use this month’s money to pay for things I bought and already forgot about last month. Confusing, right?

I stopped using a credit card because that was the best way I knew how to build in guardrails against my tendency to overspend.

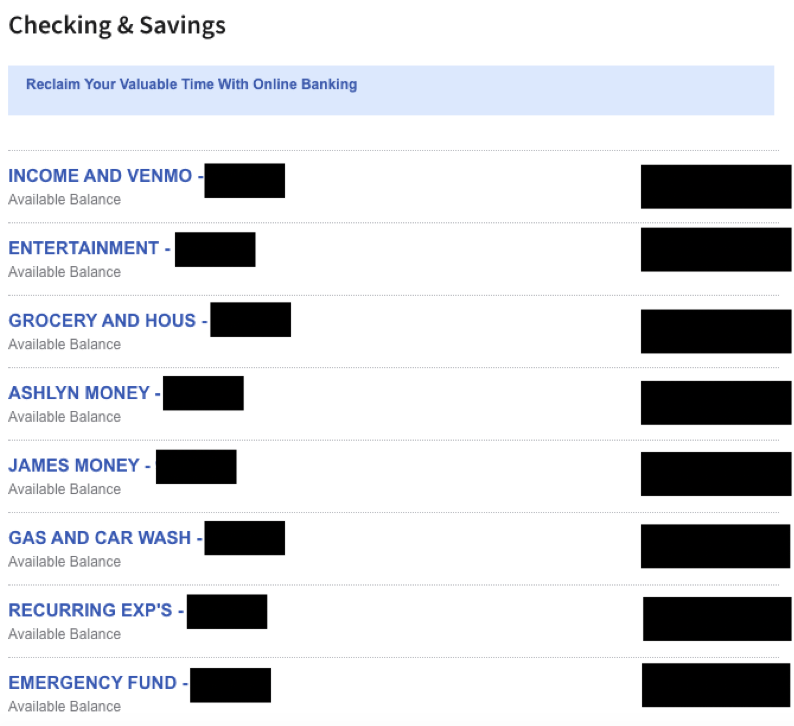

Instead, my wife and I opened up separate checking accounts for the different categories in our budget. That way we have complete visibility as to how much money we have left throughout each month to spend.

Here’s a snapshot of what I see when I log in to my bank –

I thought about making those black boxes super long so everyone would think I have tons of money, but my wife would have teased me endlessly for that. Or she would have asked if she could have all that money to go shopping.

Income and Venmo – this is the account is where our paychecks go each pay period. From there I transfer enough into the other accounts to fill them up for the month.

I also have all Venmo payments run through here. If I need to Venmo someone for buying me lunch then I transfer money from James Money to Income and Venmo so I can pay them. If I need to Venmo someone for buying me groceries then I would transfer money from Grocery and Household to Income and Venmo so I can pay them.

Grocery and Household – this one is pretty straightforward. We put an amount into this account that we know can cover our grocery/household bills for the month. There’s enough to cover everything, but it also forces us to be mindful of our spending because we can’t burn through that account in 15 days if we want to eat for all 30 of them.

Gas and Car Wash – Same as above.

Entertainment, James Money, and Ashlyn Money – These are our discretionary accounts. Instead of grouping together all discretionary expenses into one account, we break them into separate accounts. This prevents disagreements about what “discretionary” means to me versus what it means to Ashlyn.

Ashlyn can go buy whatever she wants with her money without having to ask me. And I can go buy whatever I want with my money without having to run it by her first.

The Entertainment account is kind of like our date night account. It’s for dinners, movies, or other forms of entertainment that we do together.

Recurring Expenses – This one is the easiest of them all. I set all fixed monthly expenses on auto-pay and I have them charged to this account. So at the beginning of the month, I put enough here to cover all fixed expenses, and then I don’t think about it again.

One side note – Recurring Expenses and Emergency Fund are at the bottom of this screenshot here and that’s intentional. When I log in to my bank account I actually don’t even see these two accounts. I don’t want to see them.

The goal of this for me is to not have to think about money. So I don’t care how much is left in my recurring expenses because I know it will be fully spent by the end of the month.

I don’t care about my Emergency Fund either. Once it became fully funded I stopped caring how much was in it because I knew I wasn’t going to spend it unless there was an emergency. I didn’t need to dip into it for one-off expenses because I had already planned for those.

The cool part is all I really care about when I view my accounts is how much I have left in the James Money fund.

I don’t have to worry about what Ashlyn is doing with her money because it’s all hers. I don’t even need to worry about the groceries or gas accounts because we tend to spend the same on those throughout each month.

By using a debit card to pay for these transactions I have immediate visual feedback in my bank account about how much I can still spend for the month before I run out of money in the James Account.

For some, all these accounts might be overkill. But for me, I like the feeling of knowing exactly where my money is going without having to actually track it day by day. In many ways, this system is set it and (mostly) forget it.

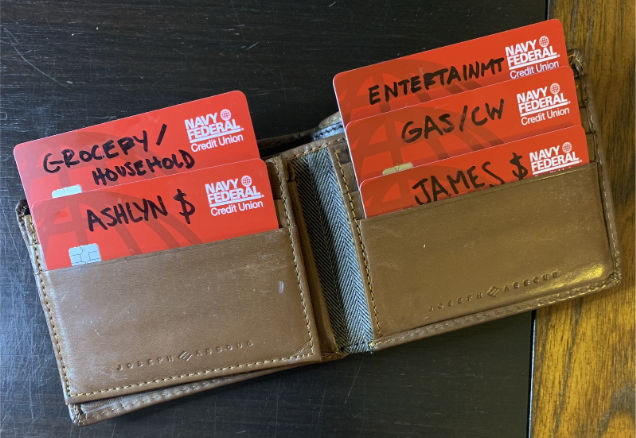

In full disclosure, the way I set it up requires carrying around a few debit cards. I’m pulling my wallet out of my pocket as I write and here’s a picture of what it looks like:

To anyone who adopts this system, take a lesson from me – identify your cards a little more subtly than using large sharpie letters across the top of them. You get some weird looks when you pull out your wallet to pay for dinner.

Although this system is a little weird to some, here’s the thing. I can get an accurate picture of my financial situation in 5 seconds. And even then, that’s just because Face ID on my iPhone takes 3 seconds to let me into my banking app.

In the past, it was much more complicated to understand where I really stood with my finances each month.

I had to take a look at my bank account.

And then I had to look at my credit card charges that had already gone through.

And then I had to look at my pending credit card charges and try to figure out if they were already included in my total credit card balance or not.

And then I had to figure out how many recurring charges I had left in the month.

And by then my brain was tired and just wanted to give up on caring about where I was spending money.

Not anymore. All I have to do is take one quick look at my accounts and I know how I’m tracking toward my monthly spending.

And the best part? It requires minimal ongoing effort.

Conclusion

There are a lot of ways to do this. If you don’t like this or you have a better way then that’s great. I just wanted to share what works for me.

One of my favorite writers/thinkers is James Clear, author of Atomic Habits. James has a weekly newsletter that he sends out, and in one of his recent emails he wrote something that sums up the reason I have this system:

The idea that “change is hard” is one of the biggest myths about human behavior.

The truth is, you change effortlessly and all the time. The primary job of the brain is to adjust your behavior based on the environment.

Design a better environment. Change will happen naturally.

This system for me is my better environment. My spending patterns changed naturally after setting things up appropriately on the front end.

I no longer have to “budget”. Most of the work is already done for me each month as a result of setting up the right system on the front end.

Designing a budget that makes me not have to think about my budget was a win for me, and I know it will be for you too if you want it to.

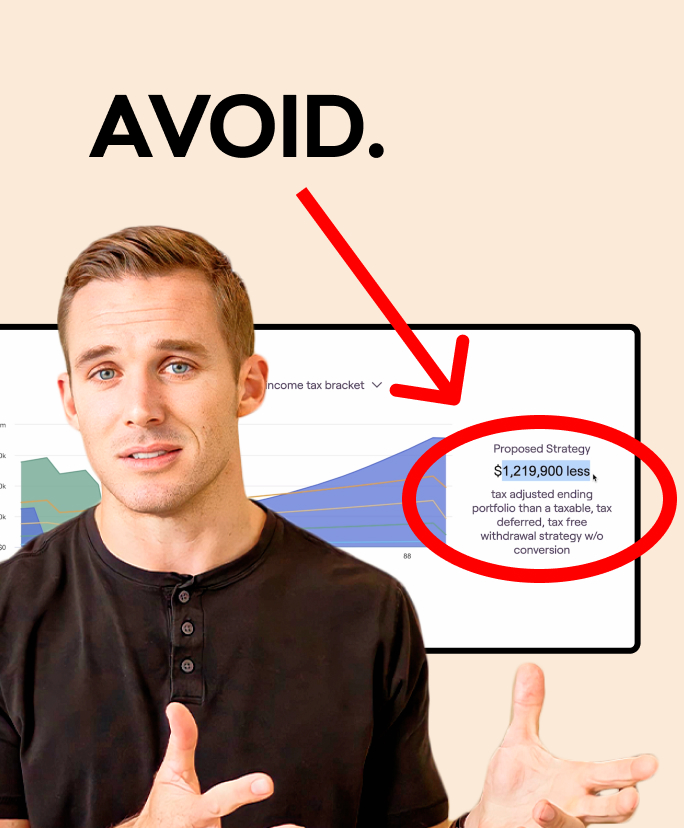

P.S. If you this is something that you would like to implement in your own life then here’s another link to the spreadsheet that I use. You will need to add/remove some of these categories, but the basic framework is there.